St. Petersburg, Florida

December 4 and 5

Monday, December 4, the Captain and the Admiral pay a visit to the Dalí Museum.

The Building

The original Dalí Museum opened in St. Petersburg in 1982, after community leaders rallied to bring the Morses’ superlative collection of Dalí works to the area. (More about the Morses under “History” below.) The Dalí’s stunning new building opened on January 11, 2011.

Designed by architect Yann Weymouth, it combines the rational with the fantastical: a simple rectangle with 18-inch thick hurricane-proof walls out of which erupts a large free-form geodesic glass bubble known as the “Enigma”.

Weymouth worked as chief of design for I.M. Pei on the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and on the Grand Louvre Project in Paris.

From the Museum website:

“The new structure enables the Museum to better protect and display the collection, to welcome the public, and to educate and promote enjoyment. In a larger sense it is a place of beauty dedicated, as is Dalí‘s art, to understanding and transformation.”

The Enigma, which is made up of 1,062 triangular pieces of glass, stands 75 feet at its tallest point, a twenty-first century homage to the dome that adorns Dalí’s museum in Spain.

Inside, the Museum houses another unique architectural feature – a helical staircase – recalling Dalí’s obsession with spirals and the double helical shape of the DNA molecule.

Avant-Garden

On the waterfront of Tampa Bay, The Dalí’s Avanti-Garden creates a unique environment of learning and tranquility. The Mathematical Garden allows students to experience the relationship between math and nature and invites exploration and well-being.

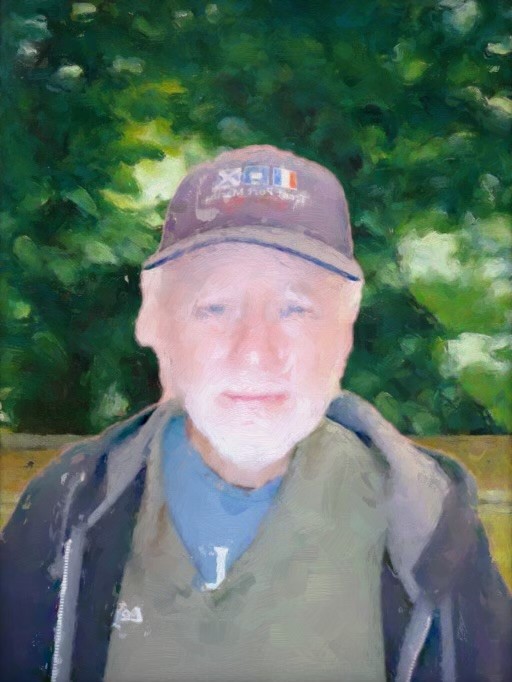

Your Impressionist Portrait

One of the coolest experiences for Captain Pat and I is the YOUR PORTRAIT, which transforms your portrait into a one-of-a-kind digital work of art.

Museum visitors further their understanding of unique artistic genres with this exclusive artificial intelligence (AI) experience. You sit in one of four photo booths, look into the camera, click a few buttons on the photo screen, and eventually your impressionist portrait appears.

You submit your email and the portrait is sent to you.

I tried this again during my second visit to the museum!

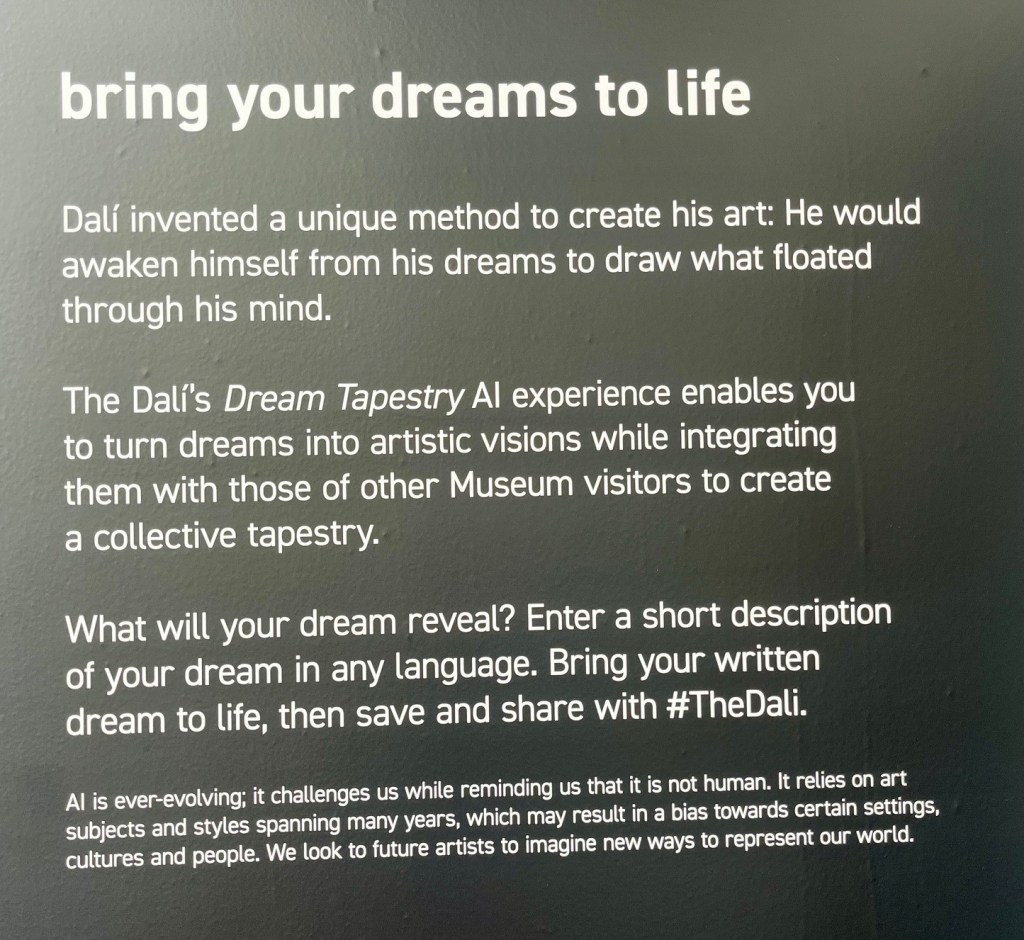

Dalí Dream Tapestry AI Experience

Another Dalí Museum experience allows you to create art from a dream. You simply hover your smartphone over the QR code and an app allows you to type in a few words describing your dream. See explanation below.

I type in “engine overheats on the boat.” (Ok, so this was more of a nightmare than a dream.) This image appears:

A second rendering follows:

The second rendering includes input from other people in the database who may have submitted similar dreams (I think.) See the museum explanation below:

I type in “dolphins swimming by the boat” - this appears:

Then the second rendering:

I like the first version better – without the dramatic “heated engine” symbols included with the dolphins.

During my second visit to the museum, I type in “woman visits therapist” and these images appear:

I could have done this all day long, as I am fascinated with dreams and fantasy and imagination.

History of the Dalí Museum

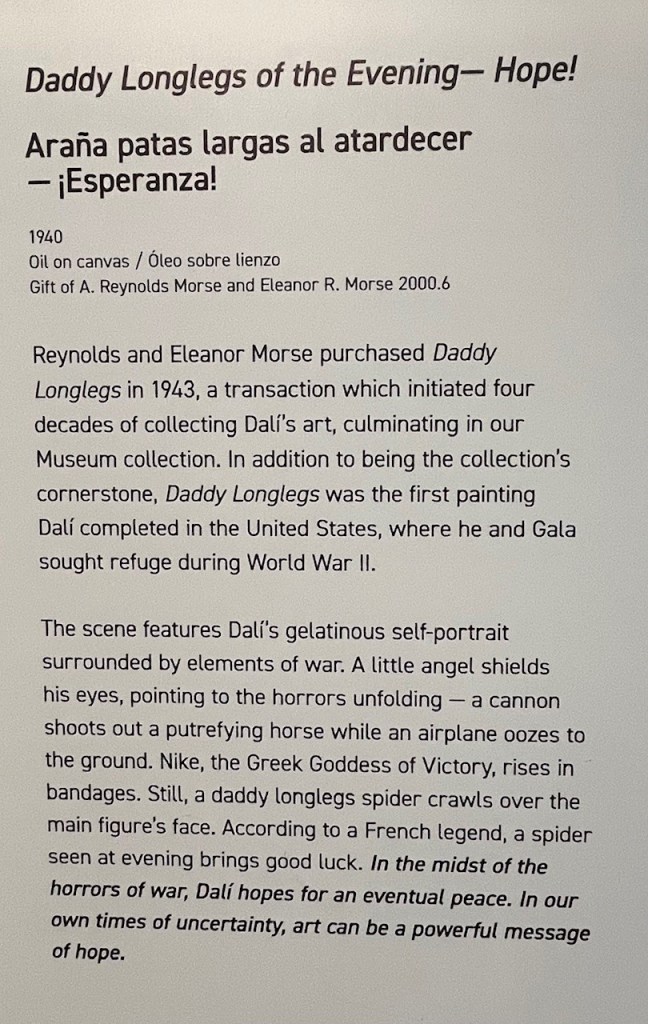

In 1942, Reynold and Eleanor Morse visited a traveling Dalí retrospective at the Cleveland Museum of Art organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and became fascinated with the artist’s work. On March 21, 1943, the Morses bought their first Dalí painting, Daddy Longlegs of the Evening, Hope! (1940) as a wedding gift to each other.

I am intrigued with this painting. We have many Daddy Longleg spiders at the Lake.

The painting cost $1,250. The frame – $1,700! Turns out Gala, Dalí’s wife of 48 years, was the business genius in the relationship. She insisted Dali’s artwork be sold with the frame, and the frame was always an added cost.

Daddy Longlegs of the Evening, Hope! (1940) was the first of many acquisitions, which would culminate 40 years later in the preeminent collection of Dalí’s work in America. On April 13, 1943, the Morses met Salvador Dalí and his wife Gala in New York initiating a long, rich friendship.

The Morses first displayed their Dalí paintings in their home, and by the mid-1970s decided to donate their entire collection. A Wall Street Journal article titled, “U.S. Art World Dillydallies Over Dalí,” caught the attention of the St. Petersburg, Florida community, who rallied to bring the collection to the area.

Museum Docent Tour

We learn from a Museum guide there is a guided tour by a docent at 12:30 p.m. This turns out to be amazing. She has a wealthy of knowledge about Dalí, the symbolism in his artwork, and pertinent details of his life.

Life of Dalí

Salvador Dalí was born in 1904 in Figueres, Spain, where he died in 1989. A year before his birth his two-year-old brother died, also named Salvador. Dalí would later claim he always felt to be the “replacement” child. Dali painted “Portrait of My Dead Brother” in 1963.

Many of Dali’s displayed paintings are accompanied by an explanation of the symbolisms within the art – as seen above. The knowledgeable docent is an skilled storyteller with even more details. She tells us it is rumoured that Dalí used the image of Robert F. Kennedy in this painting.

Dalí’s Early Childhood

Dalí ‘s father, Salvador Luca Rafael Aniceto Dalí Cusí (1872–1950) was a middle-class lawyer and notary, an anti-clerical atheist, and Catalan federalist, whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domènech Ferrés (1874–1921) who encouraged her son’s artistic endeavors. Felipa was Catholic.

The elder Dalí kept a book showing people with venereal disease out on the piano in their home, to dissuade his children from sexual activity.

Dalí adored his mother, and his world is rocked when in 1921 she dies of uterine cancer. His father married her sister the next year. Dalí approved of the marriage, as he always loved his Aunt.

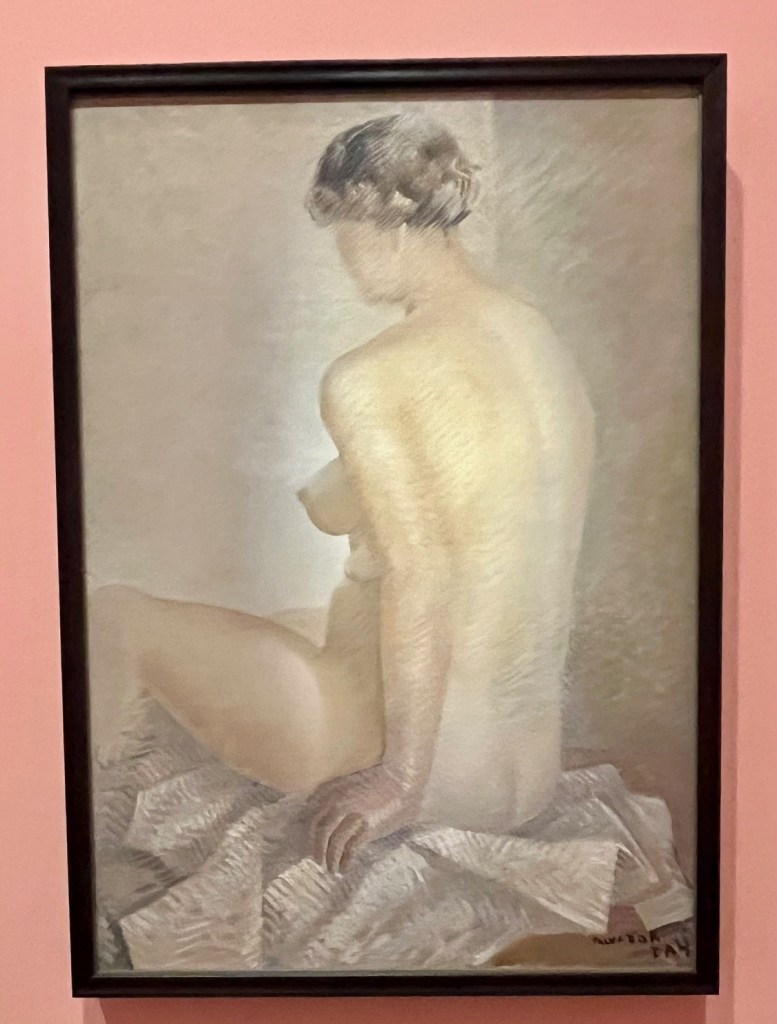

Dalí also had a sister, Ana María, who was three years younger. Dali painted her twelve times between 1923 and 1926.

The painting above hangs in the Museum and is Dalí’s second rendition of the portrait. His first drawing shows 15-year-old sister Ana Maria, in a realistic style. She was seated in an armchair with her hands crossed in her lap; a small table with books occupies the lower right-hand corner.

Dalí returned to this celebrated portrait and added the second upside-down figure in a style radically different from the first, giving the whole composition the appearance of a playing card. The distorted second portrait seems inspired by early Cubist portraits of Picasso.

This over-painting reveals the tension growing between the artist and his sister. Close during their youth, Dalí and his sister grew distant once Gala, his future wife, entered his life. The two women disliked each other from the start. When Dali published his creative autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dali in 1941, filled with outrageous and shocking stories about his behavior as a boy, Ana Maria felt compelled to challenge his carefully orchestrated stories.

In 1950 she published Salvador Dali as Seen by His Sister, presenting his youth in far more ordinary terms. Instead of the monstrous child Dali describes, she presents her brother as simply a spoiled child, and she blames Gala and the Surrealists for encouraging his aberrant fantasies.

Dalí ‘s Study of Art

In 1922 Dali enters the San Fernando Academy of Art in Madrid. Dalí draws attention “as an eccentric and dandy. He has long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee-breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century.” In 1923 Dalí is expelled for one year from the San Fernando Academy for criticizing his lecturers and causing dissent amongst the student population.

Even though Dalí studied for many years at the Special Painting, Sculpture and Engraving School of San Fernando in Madrid, he never graduated, much to his father’s disapproval. That’s because, during his very last exam at the school, he refuses to take the exam, saying the quality of his artwork speaks for itself. He insults a professor, saying that the teachers weren’t qualified enough to test him, and was immediately expelled.

Dalí and His Father

Dalí ‘s relationship with his father continues to decline, especially with Dalí’s marriage to Gala. In 1929 Dalí hears of his expulsion from the family home and shaves his head in an act of defiance against the threat of symbolic castration. Over the next four years he produces a series of paintings featuring his father in the form of mythical and historical figures, with distorted, bald heads or hydrocephalic, anamorphic skulls.

Dalí was an avid study of Sigmund Freud, and used many Freudian symbolisms in his art.

“Referring at once to the threat of emasculation by a ruthless father and the sublimation of unresolved Oedipal desires, these disturbing paintings collectively explore the theme of masochism: the desire for and resistance to symbolic incorporation and authoritarian control.” – the Museum.

One of these paintings is “The Average Bureaucrat (1930),” a clear reference to Dalí ‘s father, a notary.

Our tour docent explains the symbols in this painting. The father is looking down. He is naked, vulnerable. His brain has been emptied and replaced with snail shells in the craterlike opening of his head. The shells, in Freudian symbolism, allude to female genitalia. The openings on the head transforms the bourgeois law and order into an elaborate, soft Swiss cheese.

Not a favorable tribute to this father. Dali is later cut out of his will.

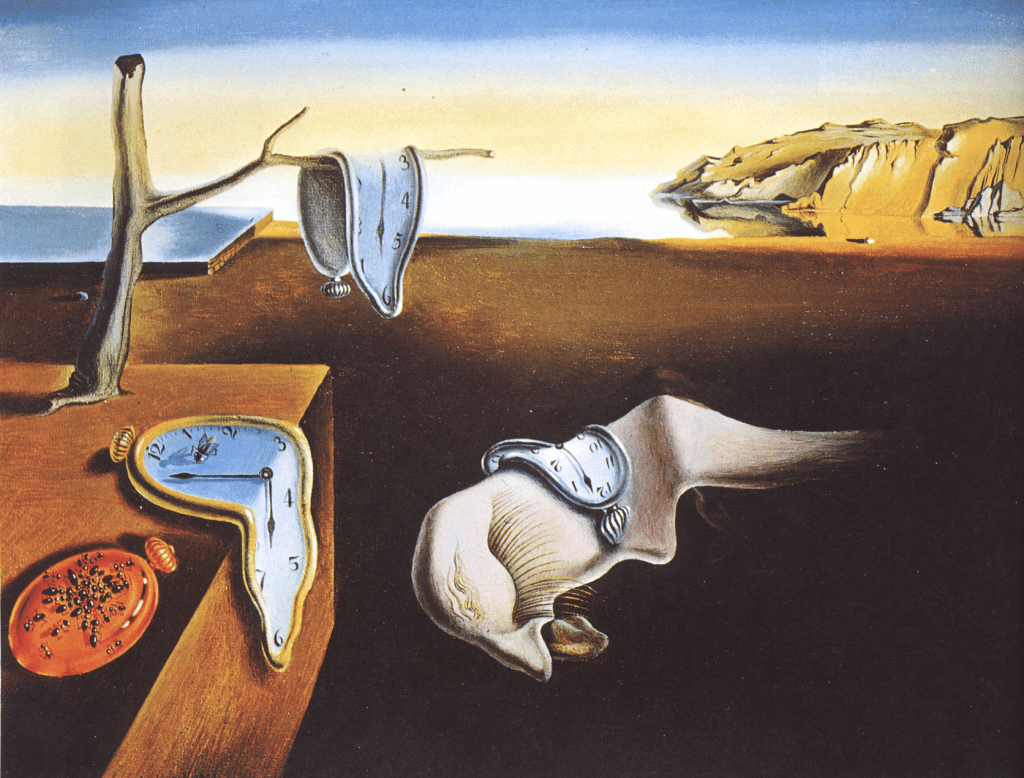

Dalí and Surrealism

Dalí moved closer to Surrealism in the late 1920s and joined the Surrealist group in 1929, soon becoming one of its leading exponents. His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in August 1931, and is one of the most famous Surrealist paintings.

Dalí ‘s Life with Wife Gala

Dalí met and married his wife, Gala, in 1934. She was ten years his senior. Gala Dalí (born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova -1894 – June 1982), was the wife of poet Paul Eluard when she met Dalí and became his lifelong muse. She also inspired many other writers and artists.

Gala was born in Kazan, Russian Empire, to a family of intellectuals. She worked as a school teacher while living in Moscow.

In 1912, she was sent to a sanatorium near Davos in Switzerland for the treatment of tuberculosis. She met Paul Eluard while in Switzerland and fell in love with him. They were both seventeen. In 1916, during World War I, she traveled from Russia to Paris to reunite with him; they were married one year later. They had one child, daughter Cécile (11 May 1918 — 10 August 2016). Gala detested motherhood, mistreating and ignoring her child.

With Éluard, Gala became involved in the Surrealist movement. She was an inspiration for many artists including Éluard, Louis Aragon, Max Ernst, and Andre Breton.

She, Éluard, and Ernst spent three years in a menage a trois, from 1924 to 1927. In early August 1929, Éluard and Gala visited a young Surrealist painter in Spain, the emerging Salvador Dalí . An affair quickly developed between Gala and Dalí, and Gala left her husband and child. Nevertheless, even after the breakup of their marriage, Éluard and Gala remained close.

Salvador and Gala lived in France throughout the Spanish Civil War before leaving for the United States in 1940 where Dalí achieved commercial success. He formed partnerships with Walt Disney, Alfred Hitchcock, and other celebrities in the film industry.

In the early 1930s, Dalí started to sign his paintings with his and Gala’s name as “it is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures”. He stated that Gala acted as his agent, and aided in redirecting his focus. According to most accounts, Gala had a strong libido and throughout her life had numerous extramarital affairs (among them with her former husband Paul Éluard), which Dalí encouraged, since he was a practitioner of candaulism. She had a fondness for young artists, and in her old age she often gave expensive gifts to those who associated with her.

They returned to Spain in 1948 where Dalí announced his return to the Catholic faith and developed his “nuclear mysticism” style, based on his interest in classicism, mysticism, and recent scientific developments.

In 1968, Dalí bought Gala the Castle of Pubol, Girona, where she would spend time every summer from 1971 to 1980. At her request, Dali agreed not to visit there without getting advance permission from her in writing.

Dali’s Art and Reputation

Dalí’s artistic repertoire included painting, graphic arts, film, sculpture, design and photography, at times in collaboration with other artists. He also wrote fiction, poetry, autobiography, essays and criticism. Major themes in his work include dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, religion, science and his closest personal relationships.

To the dismay of those who held his work in high regard, and to the irritation of his critics, his eccentric and ostentatious public behavior often drew more attention than his artwork. His public support for the Francoist regime, his commercial activities and the quality and authenticity of some of his late works have also been controversial. Like Picasso, he was known for signing a napkin hoping for a free meal in a restaurant, or paying with a signed check, knowing it wouldn’t be cashed but kept for the value of his signature.

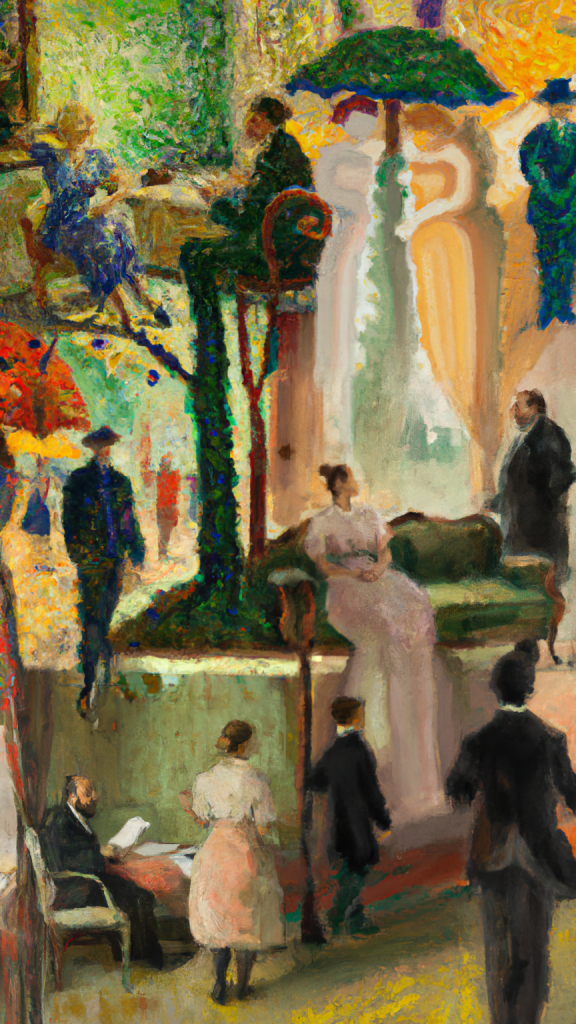

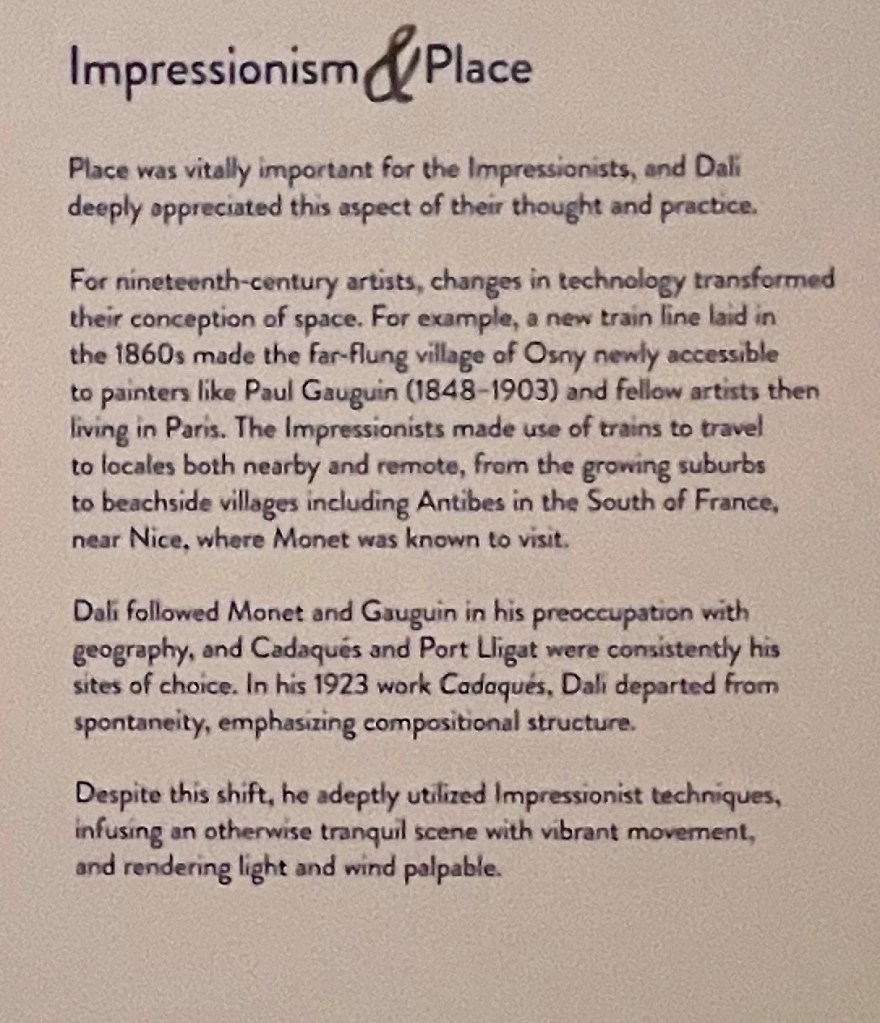

Impressionism, Realism, and Cubism

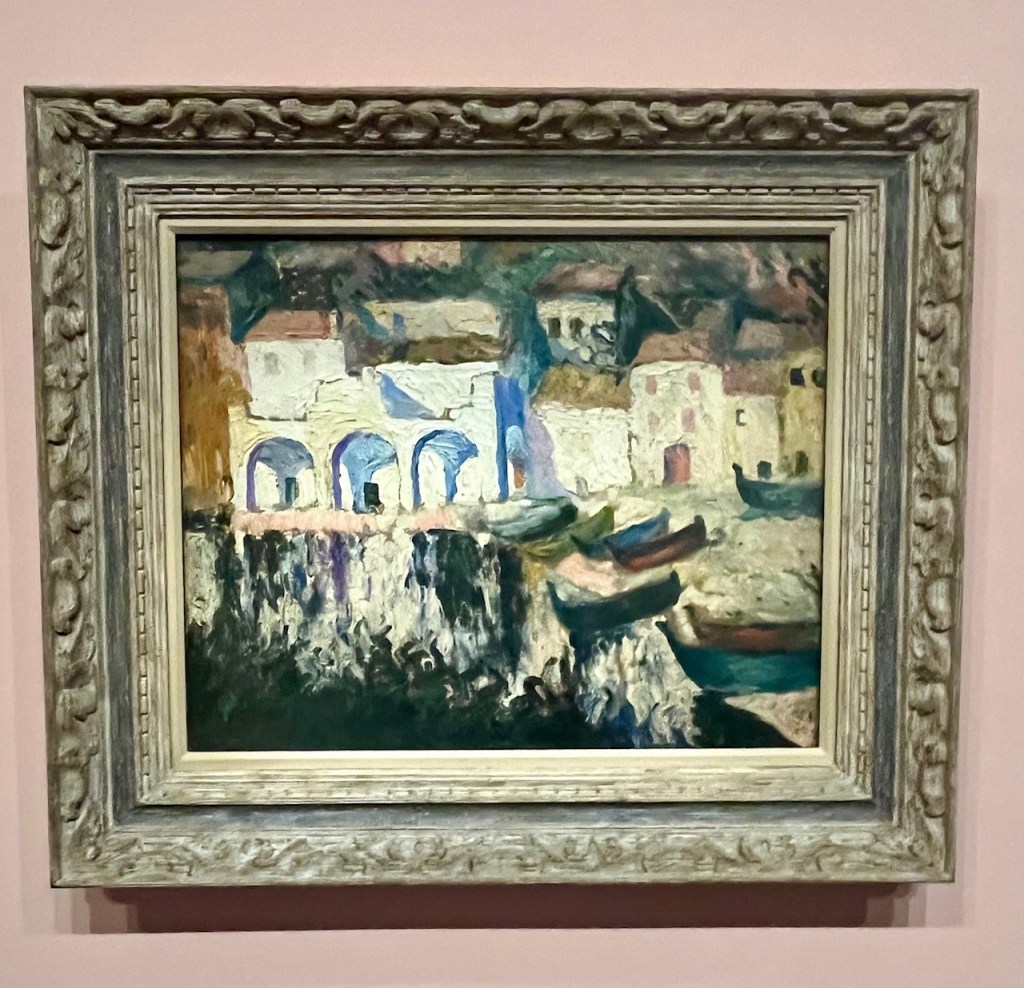

We felt fortunate that the Dalí Museum was featuring an exhibit where artwork was on loan from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. We viewed famous paintings from the art periods of impressionism, realism and cubism. Dalí was influenced by each of these art periods.

The docent offered an art refresher:

Impressionism is painting with a bright explosion of color, giving you the impressionism about how it feels to be there.

Realism is when the painting looks so real and lifelike it reminds you of a photograph.

Cubism painting is make up of simple shapes, and reminds you of a jumbled puzzle.

Cadaques, Spain, was the subject of many Dalí‘s paintings.

Here are photos of prominent paintings from artists of the impressionistic era.

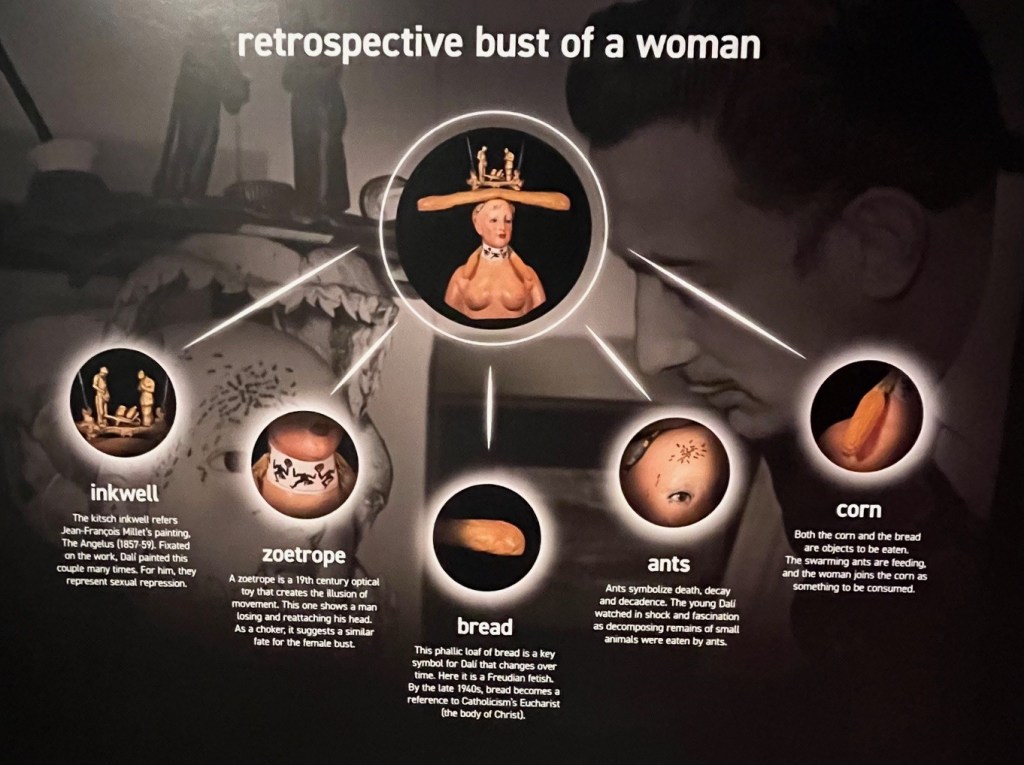

Dalí’s Surrealist Sculpture – The Bust of a Woman

Dalí once said about Surrealist sculpture, “it is absolutely useless and created wholly for the purpose of materializing in a fetishistic way, with maximum tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delirious character.”

The following explanation of the symbols within the sculpture hangs in the museum.

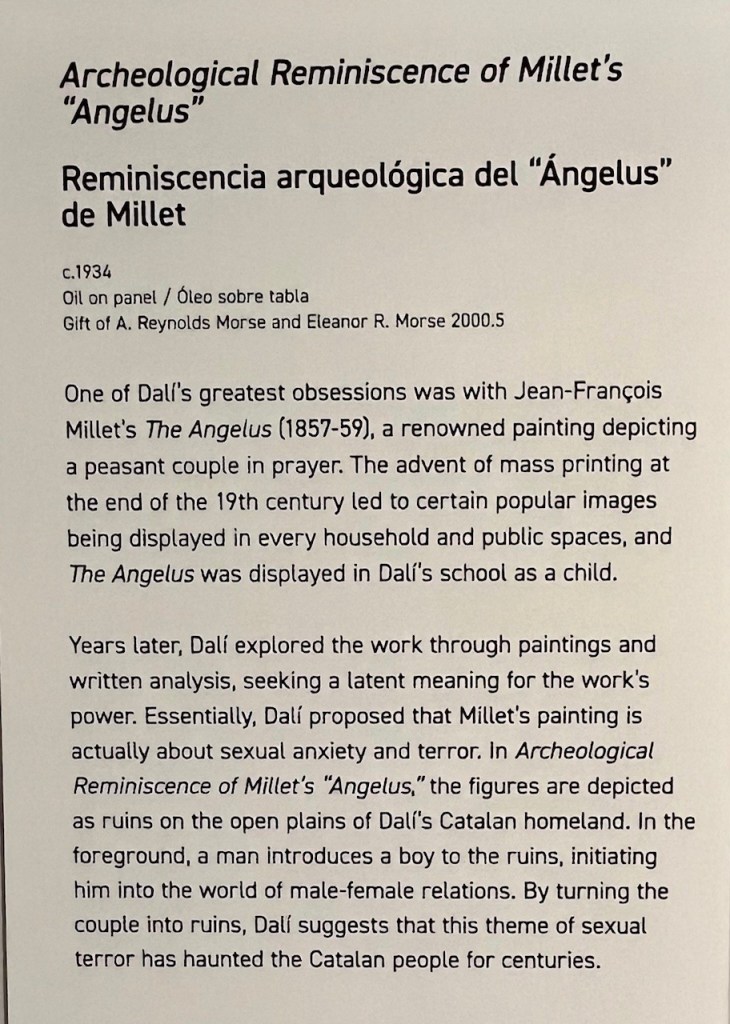

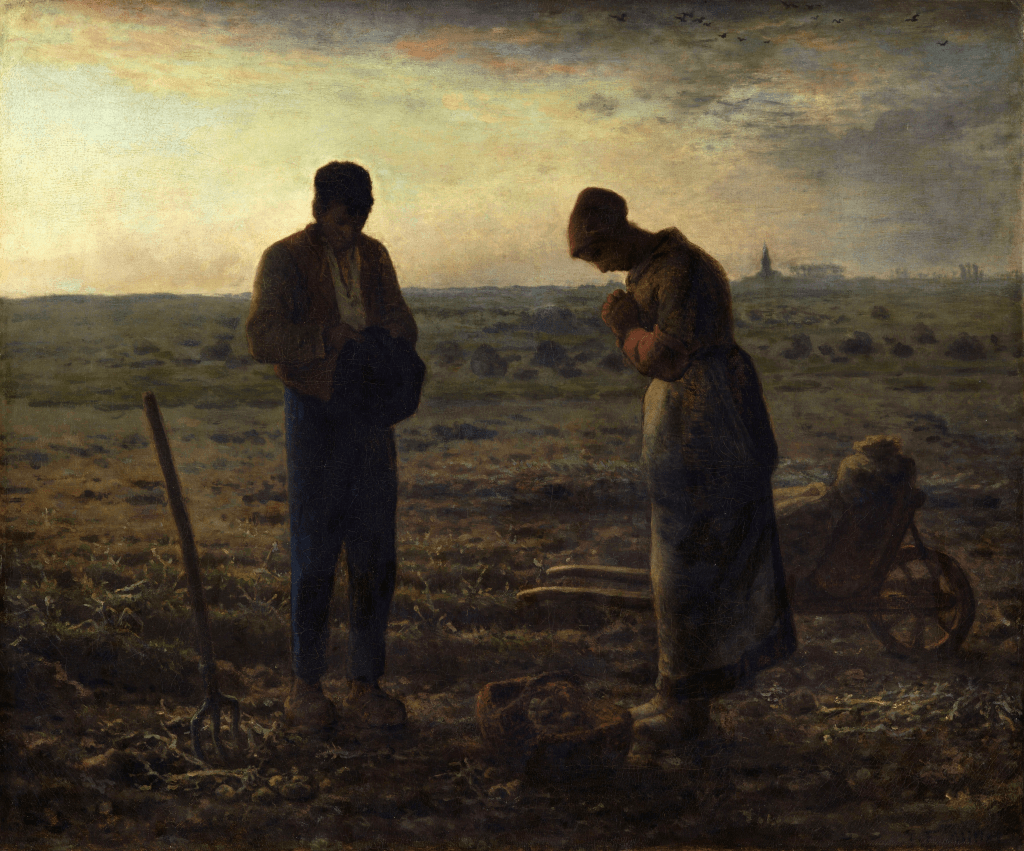

The kitsch inkwell refers to Jean-Francois Millet’s painting, The Angelus (1857-59). Fixated on the work, Dalí painted this couple many times. Dalí viewed the Millet painting many times in his childhood, at school and at home. For him, the couple in the painting represent sexual repression.

A zoetrope is a 19th century optical toy that creates the illusion of movement. This one shows a man losing and reattaching his head. As a choker, it suggests a similar fate for the female bust.

This phallic loaf of bread is a key symbol for Dalí that changes over tiime. Here it is a Freudian fetish. By the late 1940’s, bread becomes a reference to Catholicism’s Eucharist (the Body of Christ.)

Ants symbolize death, decay, and decadence. The young Dalí watched in shock and fascination as decomposing remains of small animals were eaten by ants.

Both the corn and the bread are objects to be eaten. The swarming ants are feeding, and the woman joins the corn as something to be consumed.

Dalí Famous Paintings

Following are six of Dalí’s most famous paintings, each followed by the Museum explanation of the background and symbolism of the artwork.

Millet’s painting depicts a couple praying the Angelus over a basket of potatoes. Dalí’ claimed this was not a prayer service but rather a funeral, and not a basket of potatoes but a box (coffin) containing their son.

In 1963 the Louvre Museum had the painting x-rayed and did actually find a box-like shape that was painted over by the basket of potatoes.

The face in the painting – at the bottom, yellow hair, long eyelashes, with spider on it – Dalí uses many times in his painting. The dying cello means the music no longer plays – because of the war. Horses are usually strong, but this one is decaying.

This painting eluded me. During my first visit to the Museum, the docent emphasized its correlation to the war. During my second trip to the Museum I was determined to find the painting again. But I couldn’t. Round and round I went in circles.

I finally realized it was the Daddy Longlegs painting! I had passed the painting at least twice. But I focused on the Daddy Longlegs imagery and didn’t connect the war to it.

Such it is with my life. Always going around in circles, not connecting the dots, and usually the answer is right in front of me.

This painting wins the prize for the longest title on a painting. Kidding aside, I do adore this painting, because of my love of Lincoln and how his image is portrayed with the pixelation.

The Venus de Milo is one of the most famous statues from ancient Greece. Dalí used it in many of his paintings. Also insects. As a child he was afraid of grasshoppers.

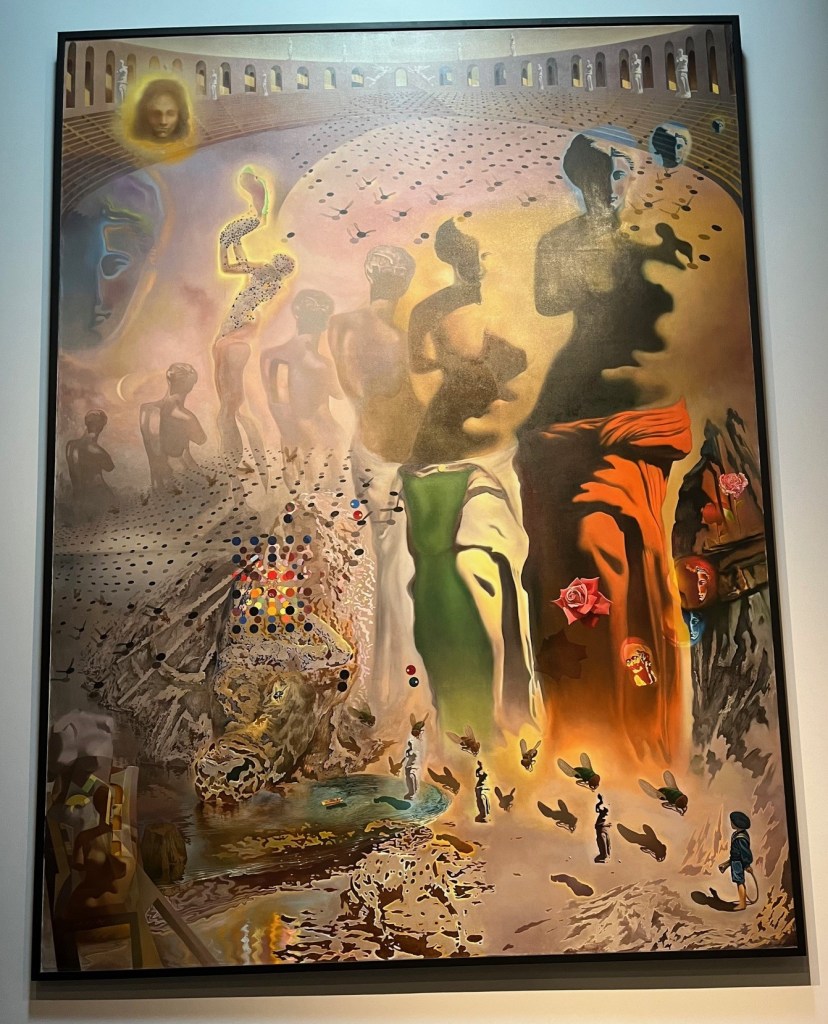

This work is an ambitious homage to Dalí’s Spain. It combines Spanish history, religion, art, and myth into a unified whole. It was commissioned for Huntington Hartford for the opening of his Museum Gallery of Modern Art in New York’s 2 Columbus Circle. At this time, some Catalan historians were claiming that Columbus was actually from Catalonia, not Italy, making the discovery all the more relevant for Dalí, who was also from this region of Spain.

The eponymous painting deals with Christopher Columbus’s first landing in the New World. It depicts the event metaphorically rather than aiming for historical accuracy. Columbus is depicted not as a middle-aged mariner, but as an adolescent boy in a classical robe to symbolize America as a young continent with its best years ahead of it.

Dalí, in a period of intense interest in Roman Catholic mysticism at the time, symbolically portrayed Columbus bringing Christianity and the true church to a new world as a great and holy accomplishment.

Gala Dalí, whom he often depicted as the Virgin Mary, poses for the role of The Blessed Virgin (or according to some commentators Saint Helena) on the banner in the right hand of Columbus. She appears as a Saint, suggesting that she is Dalí’s muse and that she is responsible for his own, “Discovery of America”.

Dalí painted himself in the background as a kneeling monk holding a crucifix. Dalí’s belief that Columbus was Catalan is represented by the incorporation of the old Catalan flag.

The painting contains numerous references to the works of Diego Velazquez, (specifically The Surrender of Breda), a Spanish painter who had died 300 years earlier, and who influenced both Dalí’s painting and his moustache. Dalí borrows the spears from that painting and places them on the right hand side of his work. Within these spears, Dalí has painted the image of a crucified Christ, which was based on a drawing by the Spanish mystic, St. John.

In the bottom center of the painting, on the beach a few steps in front of Columbus, is the bumpy and pockmarked brown sphere of a sea urchin with a curious halo-like ring around it.

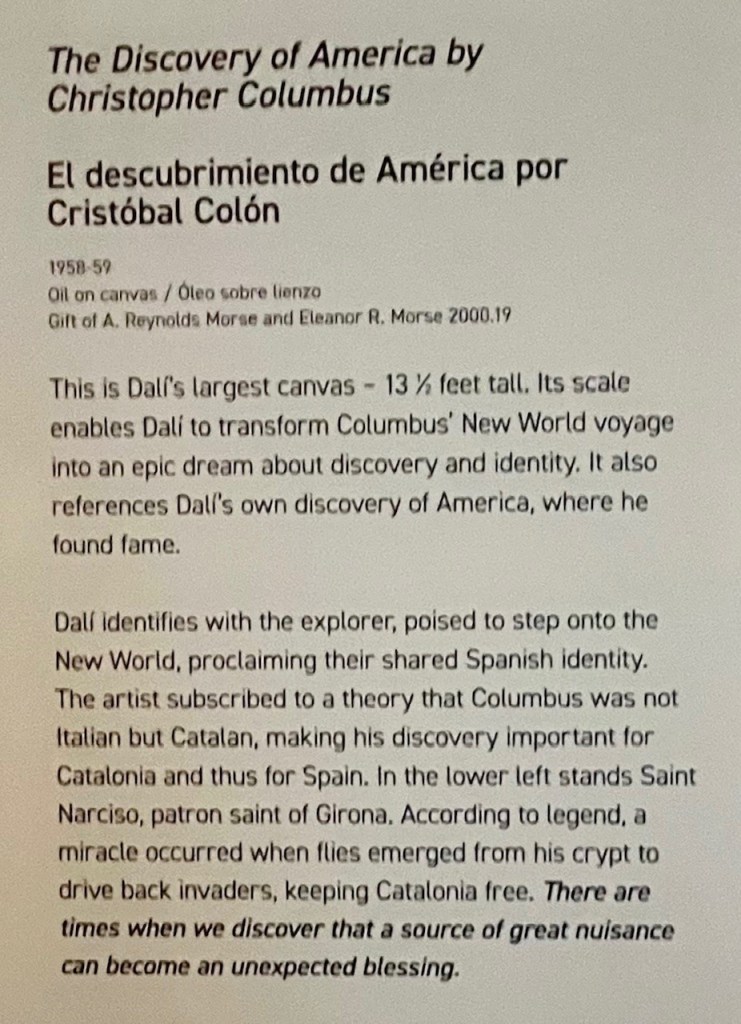

Dalí was inspired to paint The Ecumenical Council upon the 1958 election of Pope John XXIII, as the pope had extended communication to Geoffrey Fisher, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the first such invitation in more than four centuries. The painting expresses Dalí’s renewed hope in religious leadership following the devastation of World War II.

Salvador Dalí was 54 years old when he began to paint The Ecumenical Council. He was established as a surrealist with a reputation for shocking audiences with fantastic imagery, something that New York Times chief art critic John Canaday later characterized as “the naughtiness that obsessed him”.

Dalí’s work began to take on darker, more violent overtones during World War II. Possibly spurred both by the death of his father in 1950 and his interest in the writings of French theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Dalí began to incorporate religious iconography in his work.

He was by this time an international star and able to secure an audience with Pope Pius XII. By the late 1950s, both religious and cosmic matters preoccupied his work while his canvases became especially large.

The Ecumenical Council is an assemblage of religious scenes and other symbols with personal significance to Dalí that he often repeated in his works. Between Jesus and the Holy Spirit is a scene from the Papal coronation. Dalí’s wife Gala is shown kneeling under this area, holding a book and a cross.

Dalí did not sign the canvas; instead he included a self-portrait in the lower left corner, looking out at the viewer as he stands in front of a blank canvas.

A Selfie with Salvador Dalí

My last activity at the Museum was to take a selfie with the Master himself. You stand in front of a talking image of Dali. A code appears that you text to emails a link provided. And then you receive your selfie!

His Legacy Lives On

Dalí often proclaimed “he would never die.” His legacy lives on in his artwork. The Museum just received approval in August to receive $25.2 million to complete another renovation and expansion.

Studying Dalí s art and hearing of his life stories and pompous, self-serving remarks reminds me of a story told of another master, Picasso. You have probably heard it:

Picasso is sketching at a park. A woman walks by, recognizes him, and begs for her portrait. Somehow, he agrees.

A few minutes later, he hands her the sketch. She is elated, excited about how wonderfully it captures the very essence of her character, what beautiful work it is, and asks how much she owes him.

“5000 francs, madam,” says Picasso. The woman is incredulous, outraged, and asks how that’s even possible given it only took him 5 minutes.

Picasso looks up and, without missing a beat, says: “No, madam, it took me my whole life.”

2 responses to “The Dalí Museum”

Youâre almost home. Keep on truckin.. Hope youâll have time for us soon. Merry Christmas, thank you for the many enjoyable treatises and Congratulations on completion of an extraordinary sojourn. David and Stephanie

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Merry Christmas to you two! Thank you for following our travels. We will be home soon!

LikeLike